|

2008-4-15

Textile Industry Meets Demand Of Booming U.S. Population

1887-1900

Yancy S. Gilkerson

In the beginning, in 1887 when Frank P Bennett first published The American Wool and Cotton Reporter as today's ATI was then named, the textile industry was expanding at a furious pace to meet the demands of a market that was growing even faster. Despite a horrendous death rate for babies and a life expectancy of only 46 years for men, 48 for women, the population was increasing at a rate of 20% to 25% each decade (from 50 million in 1880 to 63 million in 1890 to 76 million by the turn of the century). And this growing population needed clothes.

Immigrants were pouring in to people the new states admitted to the Union in the closing years of the century (North Dakota' South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Utah) and to join the rush for land in the Indian Territory that would become Oklahoma. . . millions in need of overalls or corduroys for the week's work, and blue serge suits for Sunday- go-to-meetin'. The girls and womenfolk often made-do with house dresses made of printed flour sacks, but they coveted something finer for church wear. Sacking was a big seller in those days, used for bulk commodities like sugar, then re-used around the house. In decades to come, paper would supplant fabric for such toweling and handkerchief use.

Mostly Farmers

Two-thirds of the population then lived on the farm, working from can-see to can't-see at endless chores; tractors were years in the future, and Twenty Mule Team borax celebrated the large teams that hauled freight wagons or the giant combines.

Villages, towns and cities were small by today's standards, but the towns and cities, and many villages, were linked by the expanding web of railroads and by the telegraph. Farm to-village roads were muddy ruts in winter and dust beds in drier times. If and when weather permitted, Saturday was market day, the family heading for town, sitting on stub-legged chairs in the back of wagons loaded with whatever the season could produce for barter or sale: butter and eggs most of the time; pelts from trap lines in the winter; surplus of potatoes and other garden stuff in the summer and fall, to be exchanged for staples flour, sugar, coffee, salt.

In more remote sections. . . the Appalachians, the Ozarks. . . the bartering would often include yarn for use on the wooden hand looms that persisted well into the 1940's. The demand for home-use yarn had prompted the start of many of the small cotton mills in the South in the 1830's and 1840's, most of them with only 1,500 to 2,500 spindles run by men from New England's established textile industry.

The isolation of the farms was mind-dulling: no television, no radio, no telephone, little mail beyond the county's weekly newspaper, little to read except the Bible, and not many could read. Those were the days of the one-room country schoolhouse, if and when school kept. In 1899, in all of the U.S., only 72% of the children from ages 5 to 17 were enrolled in school, but a very small percentage of those finished high school. In fact, in 1900, the entire country produced only 62,000 high school graduates. Most girls only received four to eight years of elementary education.

Inventions Abound

But, in the towns and cities, there was excitement. . . news of inventions, of new manufacturing enterprises, new markets and new adventures in domestic and world politics.

In 1887, Gottlieb Daimler in Germany produced the first successful automobile. Nikola Tesla was inventing the alternating current induction motor, soon to be put to use in the mills. George Eastman produced the popular Kodak box camera in 18S8, and before long, snapshots of new dresses could be in the mail; "smile” was the word of the day.

First Man-Made Fiber

In England in 1892, C. F. Cross discovered viscose, leading to the later manufacture of rayon, "artificial silk", much less expensive and easier to manufacture than the real thing. Rudolf Diesel patented the internal combustion engine that bears his name. Marconi developed wireless telegraphy, and King Gillette was hailed by millions of men for his invention of the safety razor, particularly by those executives headed for Worth Street meetings who no longer had to scrape their whiskers with a straight-edge razor in the swaying washroom of a Pullman car (Most towns boasted a daredevil who could shave the back of his neck with the straight-edge as the train barrelled along).

Scientific American reported the seeds of things to come: Oliver Heaviside's discovery of the ionosphere in 1892; James J. Thomson's work with the electron in 1897; and Marie and Pierre Curie's discovery of radium in 1898.

Henry Ford made his first auto, the Quadricycle, in 1896, but the people's automobile was still many years away.

Cuba's efforts to break away from Spain aroused much sympathy in the United States, and when the battleship Maine was blown up in Havana harbor in 1898, war with Spain was a certainty. The American fleet broke the back of the Spanish navy, and a defeated Spain ceded to the U.S. the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Soon thereafter, Congress annexed Hawaii (in 1893, the U. S. had organized the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, so the islands were ripe for plucking).

ATI Begins With Queen Victoria's 50th

In the same year as the establishment of the American Wool and Cotton Reporter Queen Victoria observed her golden jubilee by celebrating 50 years on the throne of a British empire that was still expanding in Asia and in Africa.

The French too were expanding their colonies in Africa and in southeast Asia, while the new German empire demanded its share of the world's potential colonies and worked diligently at building its army and navy and at achieving technological and economic equality with the British. German chemical firms were already advertising in the Reporter.

In Russia, foreign entrepreneurs were building industries employing millions of former serfs as that country continued its struggle to modernize despite the despotic conservatism of Czar Nicholas II. Construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway began in 1891, carrying the Russian empire toward an Asia that sharply contrasted modernizing Japan with the continued long sleep of the Chinese under their Manchu conquerors and the Europeans who controlled the ports.

The Japanese, imitating the Americans and Europeans, wanted an empire too. They jumped on the hapless Chinese in 1895 and took as loot the island of Formosa (Taiwan) and Port Arthur on the mainland. The European heavyweights objected to such greediness and forced the return of Port Arthur. The "civilized" world was startled by the technical and military progress the Japanese had made of since Commodore Perry had forcibly ended their centuries-long isolation.

Enter Frank P. Bennett

All these events and their implications for the American textile industry were grist for the mill of Frank P. Bennett whose early career had prepared him well for the work and for the rising influence of his American Wool and Cotton Reporter.

Young Bennett had worked part-time in a job printing shop while attending Chelsea High School in Malden, Mass. and got a job with the weekly Malden Mirror after graduation, doing everything that needed doing: soliciting advertising, writing news reports and editorials, setting type and operating the press.

Like many enterprising young men of his Day he succumbed to wanderlust and worked on newspapers as far west as Salt Lake City while seeing the country. He returned to Massachusetts in 1876 at age 22 to work for the Commercial Bulletin in Boston. Five years later, in 1881, he swapped jobs, from managing editor of the Commercial Bulletin to managing editor of the Boston Advertiser, then owned by Henry Cabot Lodge, a valuable mentor to the young journalist. In his spare time, he wrote on finance for The Tribune in New York and for the New York Daily Press. His work brought him into contact with the leading textile executives and financial figures the time and he won their respect.

A Weekly For Movers And Shakers

Frank Bennett was 33 when he decided, in1887, that the textile industry needed a publication to serve its nationwide needs for information. The American Wool and Cotton Reporter began weekly publication from offices at 19 Pearl Street in Boston, and quickly built a network of correspondents.

Bennett's years as reporter and editor gave him access to the movers and shakers of Boston and New York to the facts and rumors of a churning economy, to the hopes, the fears, the visions and judgements of men who played with gusto the game of making money in a time when what they made they could keep… no income tax.

The Reporter, just as its descendant does today, covered all aspects of the textile industry, from sheep man and cotton planter to mill operator and mill operative, to machinery maker to designer of apparel to garment manufacturer to retailer. Coverage extended to Europe, with letters from London, Liverpool, Lancashire, France, Switzerland and Germany conveyed to the Boston office by the liners and packets plying the Atlantic, with time lag from date-of-writing to date-of-publication of as little as two weeks. Letters, sorted in the mail cars of hundreds of trains, brought domestic news, and the telegraph was available for items of greater importance.

This flood of information and the need to keep his field correspondents active (they were paid by the "string" of published material, at so much per inch) resulted also in Bennett's publication of Investor Services and his operation of Bennett's Information Services which offered to provide (for $2 per report information on any stock, any store, or any piece of real estate in the country.

Bennett's editorials reflected the man: candid, plain-spoken, out-spoken. He did not hesitate to warn of impending danger, as when British investors began to dump their shares of U.S. companies, provoking the great panic of 1893 when the heavy transfers of gold to London to pay for the dumped shares left the country short of currency.

Or, when a British syndicate attempted to form a woolen/worsted trust (monopoly) to control production and prices in the American market; this was before the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. and trusts were flourishing in nearly every industry. . . the Standard Oil Trust, the Steel Trust, the Barbed Wire Trust, the Sugar Trust, etc.

Or, when he sharply admonished sheep men for including "dung locks" with the fleece;

Or, warning that productive capacity in the late 1890's could be excessive since it was increasing faster than the population.

"I Told You So!"

He could not resist an occasional “I told you so”, eg.:

“From its inception in 1887, the American Wool and Cotton Reporter has, we are convinced been a safe guide. It has sometimes been our lot to be considerably ahead of the times, and in some cases we have been obliged to withstand a widespread criticism until our friends could catch up with us. An instance of this has occurred in the last few months. Our view regarding the wool market was at the start antagonized by not a few persons for whose judgment we have always had the greatest respect. Time has fully substantiated our position, many who previously criticized us have frankly acknowledged the clearness of our prevision.

It goes without saying that our only purpose is to be of the most assistance to the various classes in whose interest the 'Reporter' was started."

By the time of the War Between The States the American textile industry, launched at Pawtucket, Rhode Island in 1790, had grown to 1,091 mills with 5,200,000 spindles processing 800,000 bales of cotton and had outstripped English mills in the economical production of coarse, heavy fabrics. The industry was centered in New England which had 570 of the 1,091 mills. Massachusetts and Rhode Island alone accounted for nearly a third of the mills and had 18% of the spindles. Fall River and Lowell, Mass. and Providence, R.l., were the leading textile centers.

Biggest of all the mills was Naumkeag Steam Cotton Co. in Salem, Mass., with 65,584 spindles. The average mill housed only 5,000 to 12,000 spindles, with mule spindles out-numbering ring spindles two-to-one. Most mills used waterpower to run the machinery, but the more dependable steam engine was rapidly coming into use. Smaller "country" mills worked only during daylight, those in the urban areas were lighted by gas.

Spectacular Growth

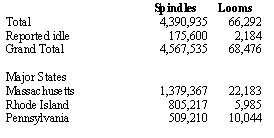

The spectacular growth of the industry in the early years of the Reporter is illustrated by the figures on spindles and looms in Chart below.

While the Southern mills were learning how to make coarse goods, the Northern mills turned more and more to production of the fine goods, a market long dominated by the British, with some input from the French.

British Influence

The British exhibit at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia had included fine woolens and worsteds, inspiring New Englanders to master the art (the great American Woolen Company was to grow out of this effort, but more about that later]. The impetus toward greater progress in fine goods production and in improvement of mill machinery came largely from individuals and families with long experience in the industry. In the 1880's, however, many mills were built in communities with no manufacturing tradition, by companies organized by men with little or no textile experience and manned by unskilled workers. . . all depended on skilled overseers and superintendents from New England mills for training and for operating know-how. Opportunity pounded on the doors of many ambitious young men who had started at the bottom of the ladder: Horatio Alger's fiction was often fact.

This was particularly true in the South where the promotion of cotton mill companies sometimes took on aspects of a religious revival, with subscription to mill stock be coming a civic duty because of the jobs that would result.

And, location in the South was attractive tomany Northern investors for many reasons,but principally because:

- the supply of raw material to be processed (cotton) was readily available without the cost of long haul freight charges,

- water power sites along the Fall Line and in the Piedmont were plentiful, and the day of hydro-electricity was at hand,

- labor was plentiful and eager to work "in the shade" after years of field work at 40 cents a day. The going rate for hands at many mills was $12.50 for 144 hours or two weeks work,

- states and cities taxed mills lightly; many cities had a gentleman's agreement not to annex mills into their limits, resulting in a ring or belt of mills around a city.

The new mill communities in the South had little or no rental housing when the mills were built. The more urbanized North had attracted capital investment in tenements for its workers. To attract their labor, Southern mills built entire villages, most often on hills for drainage, with "shotgun" houses having privies in the back yard. Wells for water were spaced about two blocks apart in the middle of the street. For most of these villages, piped water did not come for a generation.

Mill Villages

The owners and the managers of these mills were very paternalistic, just as management of early New England mills had been, particularly those of Lowell, Mass. They provided boarding houses for single men, community centers for recreation, plots to raise vegetables, a common pasture for cows kept by the farmers-turned-millhands. They built churches and subsidized the pay of preachers. In return, they expected their workers to lead sober and moral lives. Hang-overs, card playing, unblessed pregnancies, and the like, could lead to dismissal.

Some mills provided schools for elementary grades; compulsory public education was yet to come. Children went to work in the mills at 8, 10 or 12 years of age. Many old-timers who moved their families from the farm to the village recalled that their lot as young mill hands was not as dreadful as pictured by some journalists and social reformers. The alternative on the farm was daily chores, chopping weeds, picking cotton from sun up to sundown. In the mill, they had the companionship of many other children and the added benefit of working "in the shade."

National magazines and reform organizations in nearly every state persisted in efforts to pass child labor legislation, but parents were often indignant at the suggestion that "the law" might take away their authority over their offspring, might deprive the family of their earnings.

New Mill Fever

The fever for building mills continued in the North and South. By 1890, New England was home to 60 per cent of all the cotton mills in the country, but this proportion dropped to 49 per cent by 1900 as the South's share increased from 21 per cent in 1890 to 39 percent in 1900.

With all these mills increasing the production of greige goods, the result was need for more bleacheries, dye houses and print works, to the economic benefit of Providence, R. I., Waltham, Mass., Stockport, N. Y., Wilmington, Del., Fall River, Lowell, and Peabody, Mass., where many such plants were located.

In 1880, there had been 191 dyeing, bleaching, and printing plants. By 1890, the number had grown to 248 and by 1900 to 298.

There were steady improvements in the equipment operated in all these mills and finishing plants, but few major innovations. One of these was the humidifier, introduced soon after 1881, which allowed mills to take advantage of steam power, later of electric power, and to move away from the rivers, on whose proximity they had depended for the humidity needed in spinning and weaving.

Ring Spindle Invented

In 1830, Jenks had invented the ring spindle, which replaced the double-armed flyer of the throstle with a wire "traveler" running on a fixed steel ring. Sawyer vastly improved this system in 1871, achieving high speed spinning that led to production of fine yarns.

Most Southern mills employed ring spinning from the very beginning: mills in the North were reluctant to discard throstle and mule spinning that still worked well, thus giving the Southern mills an unintentional competitive advantage. Here is a statistical comparison of the relative growth of mule and ring spinning:

The most important innovation was that which dealt a mortal blow to the "kiss of death" shuttle: the Northrop shuttle-changing device. The "kiss of death" was the term applied by public health officials to the old-style shuttle that had to be threaded by sucking the filling thread through the shuttle eye. Weavers told their learners they wouldn't qualify as real weavers until they had sucked eight yards of yarn into their stomachs. The public health people pointed out that repeated "kissing" of the shuttle by different workers led to the transmission of germs in a time when highly contagious influenza and tuberculosis competed with heart disease as the leading cause of death. But, there were few health officials, and scant general knowledge of how disease spread.

The cure was the shuttle-changing device invented by J. H. Northrop, an Englishman hired in 1881 by George Draper and Sons of Hopedale, Mass. Northrop first tried his device in a mill in October, 1889. He also developed a self-threading shuttle and shuttle spring jaws to hold a bobbin by means of rings on the butt, all leading to the filling changing battery that was the basic feature of the 1891 Northrop loom, regarded as one of the greatest technical developments in the industry. Until that time the loom had to be stopped to replenish filling.

Draper's Northrop loom permitted a dramatic increase in production, and in the number of looms that a weaver could work.

Water Power Gives Way To Steam

Early mills had been powered by the force of falling water, with the power transmitted to machines by intricate systems of belts driven by shafts linked by gears to the water wheel. Steam gradually replaced water as the power source. As late as 1900, however, water still furnished 50% of the power for the mills of Manchester, Mass. and 49% for those of Lowell. Steam liberated the mill from the riverbank but not from power transmission by gear and belt. That liberation came with the electric motor, whose birth coincided with the birth of the American Wool and Cotton Reporter.

As Sidney B. Paine has written, electric motors were practically unknown in the commercial world prior to 1886. The alternating current motor was still in the laboratory stage, the first polyphase induction motor being placed on the market in 1892. A few mills had used small direct current motors, but no mill was electrified until Columbia Mills Co. (Columbia, S. C.) made the momentous decision to sign a contract July 31, 1893 with General Electric Co. for two 500-kilowatt, 3-phase, 36-cycle, 600-watt generators and 17 65-horsepower induction motors, each of the motors serving a separate section of the mill, independently of the others. To save space, the motors were suspended from the ceiling. Development of electric power for the mills then spread swiftly.

Textile Education

In the later years of the century mill owners were realizing the need for training future overseers, superintendents and managers. Leadership and interest in working in the industry were often lacking in second and third generations of family-owned mills, and the owners realized they would have to hire those who could do what the founders did.

When the Philadelphia Textile Association was organized in 1882, a main purpose was to establish a textile school. Sufficient funds, however, could not be raised at the outset. So,Theodore C. Search, one of the association organizers, started a school of his own, in one room, with crude apparata, teaching five weavers from Philadelphia mills at night. His example inspired the Philadelphia association to try again, this time successfully, and what is now the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science came into being, alma mater of many of the industry's leaders.

In 1895, Mr. Search exhibited the work of the Philadelphia School at the thirtieth anniversary meeting in Boston of the National Association of Wool Manufacturers. His address on textile education led Massachusetts textile men to have legislation passed providing matching funds for textile schools, leading to institutions at Lowell, Fall River and New Bedford. The South followed the examples: Clemson College (Clemson, S.C.) opened a textile department in 1898, Georgia Institute of Technology and the North Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1899, the A & M College at Storkville, Miss., in 1901, and the A & M College at College Station, Texas, in 1904.

ATMI's Roots

The American Textile Manufacturers Institute, Inc. is the central trade association for the cotton, man-made fibers and wool segments of the American textile industry, its membership comprising 85% of the industry's production.

ATMI is active in government relations work, statistics and economic research, public relations, safety and health, marketing, environmental preservation, international trade, data processing and almost any area of activity, except technical, which might be of concern to its individual members and which may best be handled through combined effort.

ATMI is descended from the Southern Cotton Spinners Association, incorporated in 1897 in North Carolina; the name was changed May 3, 1903 to American Cotton Manufacturers Association. ACMA was incorporated March 8, 1905.

The Cotton-Textile Institute was organized October 4, 1926, incorporated in New York, and was merged with ACMA September 30, 1949 to form the American Cotton Manufacturers Institute, Inc.

On April 30, 1958, the National Federation of Textiles, formed in 1934, merged with ACMI.

The NFT's predecessor organization is said to be The Silk Association, organized in 1872. The name of ACMI was changed on October 1, 1962 to American Textile Manufacturers Institute, Inc.

The Association of Cotton Textile Merchants of New York, which was organized on January 17, 1918, was consolidated with ATMI January 17, 1964.

The National Association of Finishers of Textile Fabrics, which was originated January 12, 1898 and staffed on January 6, 1914, was consolidated with ATMI May 20, 1965.

The National Association of Wool Manufacuters, which was formed Novemer 30, 1864, merged with ATMI on July 1, 1971.

Early Industry Leaders

Colonel J. T. Anthony, 1897-1898, founder and first president of the Southern Cotton Spinners Association which became the American Cotton Manufacturers Association. He was born on November 12, 1843 in Hanover County, Virginia; served in the Army of Northern Virginia in the division commanded by General George A. Pickett. He moved to Charlotte, N. C. some 12 years after the war. In addition to textile interests, he engaged in the lumber, ice, coal, and cottonseed trade. He died in July, 1930.

|

浙公網(wǎng)安33010602010414

浙公網(wǎng)安33010602010414